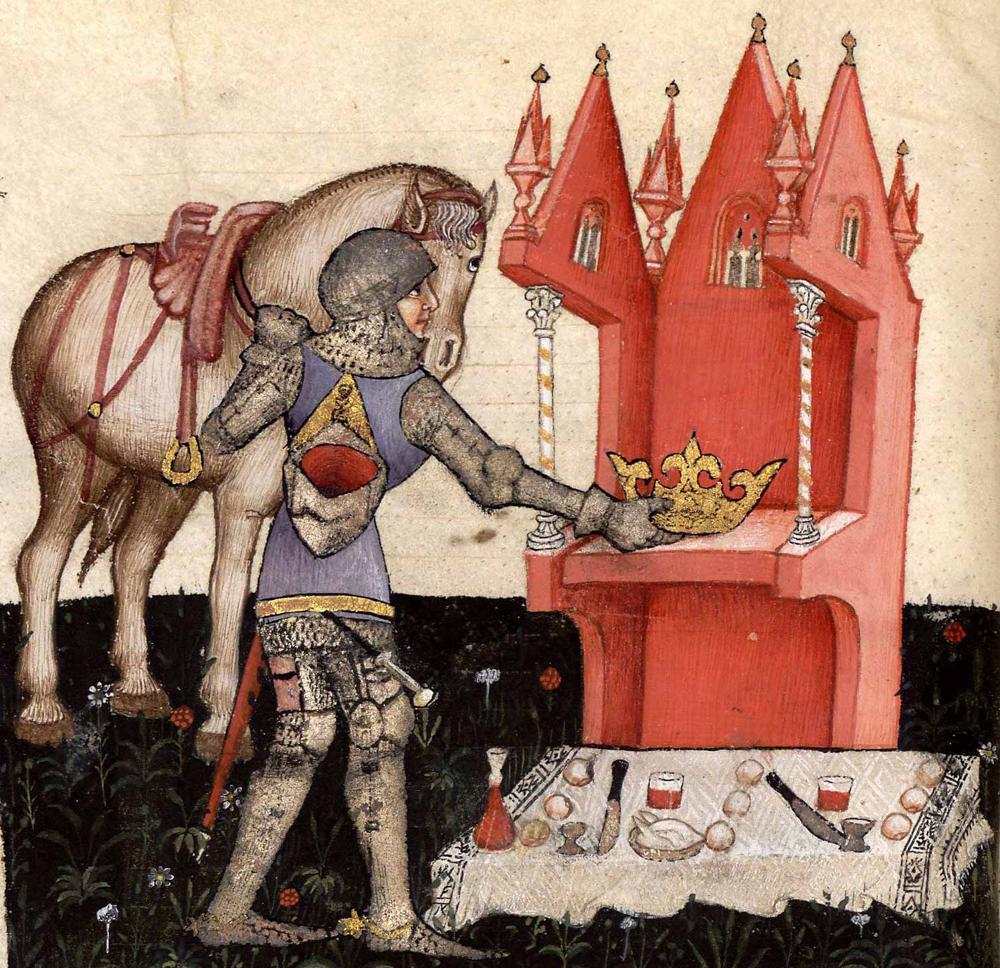

A while back, a friend gifted me a bunch of homemade brews named with the theme of knightly virtues. The beers where quite tasty, and my plan was always to drink them and think a little about the virtue of the moment. The beers are gone, but here comes some thoughts! Last time I did courage, and now it’s time for franchise.

This is the one that confuses me the most. I’m not sure if it’s a language thing, the fact that English isn’t my first language. But before I started to do some research about this, the only thing I could think of was the system of franchise restaurants. And I’m not sure that has anything to do with the chivalric virtue… So let’s dive into what some other people has written about the subject!

So, the Oxford English Dictionary defines Franchise as Freedom, immunity, privilege and as an attribute of character or action; Nobility of mind; liberality, generosity, magnanimity or Freedom or licence of speech or manners. This makes me think that this virtue is more like a state of mind, than a cause of action. Lets keep looking.

MiddleWiki has a short section on franchise and mentions that it “may be simply the virtue of owning your place in society; not being a poser and knowing what is and is not your due.” Which adds to my view of it being a state of mind. Franchise is confidence, confident that you’re in the right. Or knowing when you don’t have the capacity, and have the confidence to say so and let those who are better in the matter do their thing.

Magister Lorenzo Petrucci puts it like this: “It can be hard for a modern person to feel comfortable emulating the Medieval notion of Franchise, couched as it often is in terms of nobility and gentle birth. Our egalitarian conditioning shies away from this sort of thinking. But in the SCA we have titles, awards, offices, and Peerages, which are bestowed upon us in recognition of our nature and our deeds. I think that perhaps Franchise is the ability to accept and take ownership of the station to which one has been raised, gracefully and without false modesty.” His words on ownership repeats my thought about confidence. Feel confident in what you have achieved, peer or not, but be graceful about it. He also mentions to have “noble bearing” to one’s actions and demeanor.” So it seems like a lot of franchise is connected to another virtue, noblesse. Which is simply put as “having a regal or noble bearing, good manners and polished social interaction” by MiddleWiki. But as Magister Lorenzo also says, franchise and noblesse has to be balanced with humility.

Count Sir Garick von Kopke describes the virtue with these words: “This then is Franchise, sometimes referred to as “consistent nobility.” The first part of Franchise is simply having all of the other Chivalric Virtues and having them consistently. While this is by no means easy, it is not a separate attribute, but simply a constancy of all of them.” Also “There is a marked, if intangible, difference between the titled and the “enfranchised.” It is a carriage (but not a swagger), a sense of noblesse oblige, a certain confidence, perhaps. It can easily be overdone into arrogance or seem patronizing.” So with his words, we circle back to confidence. Confidence, but with a noble filter?

Leonhart Hunt of Wildmoor connects the virtue of franchise with the word accountability. “When you err, make amends in as public or powerful a fashion as that in which you made the error. Explain yourself in the simplest, most clear terms, and never make excuses. Own not only your own mistakes, but the mistakes of others when theirs resulted from yours.” But the words of his I take to heart is: “You must comport yourself in the present as the person you wish to become in the next moment, hour, day, and year.” Pretty much, dress for the job you want, not the one you have, but in action. Always strive to be better, in big steps or in small.

I’m not completely sure how his words connect to franchise, other than the general sense of confidence and ownership of you and your actions. So maybe it’s not so far fetched after all.

“Franchise: Emulating all parts of the code of chivalry in the hope that others will follow your example.” This follows Sir Garicks notion about franchise being the virtue that consists of all other virtues. But in this case, it’s also more clearly about setting a positivt example for others. Don’t just be good for you, but for the betterment of all.

Andrew Blackwood puts it nicely. “But not Franchise. Franchise isn’t about doing something. Franchise isn’t something you can learn. Franchise is about being who you are. […] Franchise is about being the KNIGHTLY YOU. It’s about being the best, most Chivalrous, Knightly You that you can be. It’s about being the Knight you know you Are. So that’s why it’s not enough for me to just be myself. I have to be my Knightly self. And that’s a better self than who I was Before.”

Okay, I need to stop, cause there’s so many wise people who has written about this topic, and I could continue forever. So I’ll just add this last one. Earl Cathyn Fitzgeralds wise words: “Franchise is the virtue of practicing the other eight virtues without any though of profit or personal gain. Franchise is the purest motive, selflessness in every action.” And: “Becoming virtuous for virtue’s

sake alone is the goal.”

So my initial thought was about right. “this virtue is more like a state of mind, than a cause of action.” This isn’t really something you do, but something you are, or grow into.

/Honorable Lady Gele Pechplumin

(Magdalena Morén)